About 4 years ago, a friend of mine told me a story about trying to hike the Donjek Glacier Route in Kluane National Park. It sounded like an incredible journey with views of massive mountains, endless open terrain, and wildlife at every turn. I was pretty captivated by the images his story conjured and the idea of experiencing it for myself was seeded in the back of my mind.

About a month ago, the stars aligned and Emma, our friend Joya and myself ended up having the time off work to attempt the route for ourselves.

The Donjek Glacier Route is an approximately 110km horseshoe shaped route that takes you from the Alaska highway near Burwash Landing, over a mountain pass, to the Donjek glacier, over two more mountain passes, across the mighty Duke river, over one more pass, and out back to the highway about 30km south from where you started. The route starts down a mining road and quickly turns into a trail, peters into game trails, to finally fade out to a seemingly untouched landscape. As an aspiring hiking guide, I was really excited to put my navigation skills to the ultimate test.

Our first day started with beautiful sun. Our backpack weight hovered around 50lbs, but the sun was shining and the going was easy. After a few hours of hiking along the road, we ran into our first grizzly bear. We were all relieved to see the bear quickly move away from us and up and over the opposite hillside. We were amazed at how big it was and how quickly it moved across the bushy and tussocky landscape. A few hours later we reached camp for the night; a nice wide creek bed with plenty of water and plenty of room.

The last of the sun

Big moose antlers

Day 2, the Warden’s Cabin the park boundary

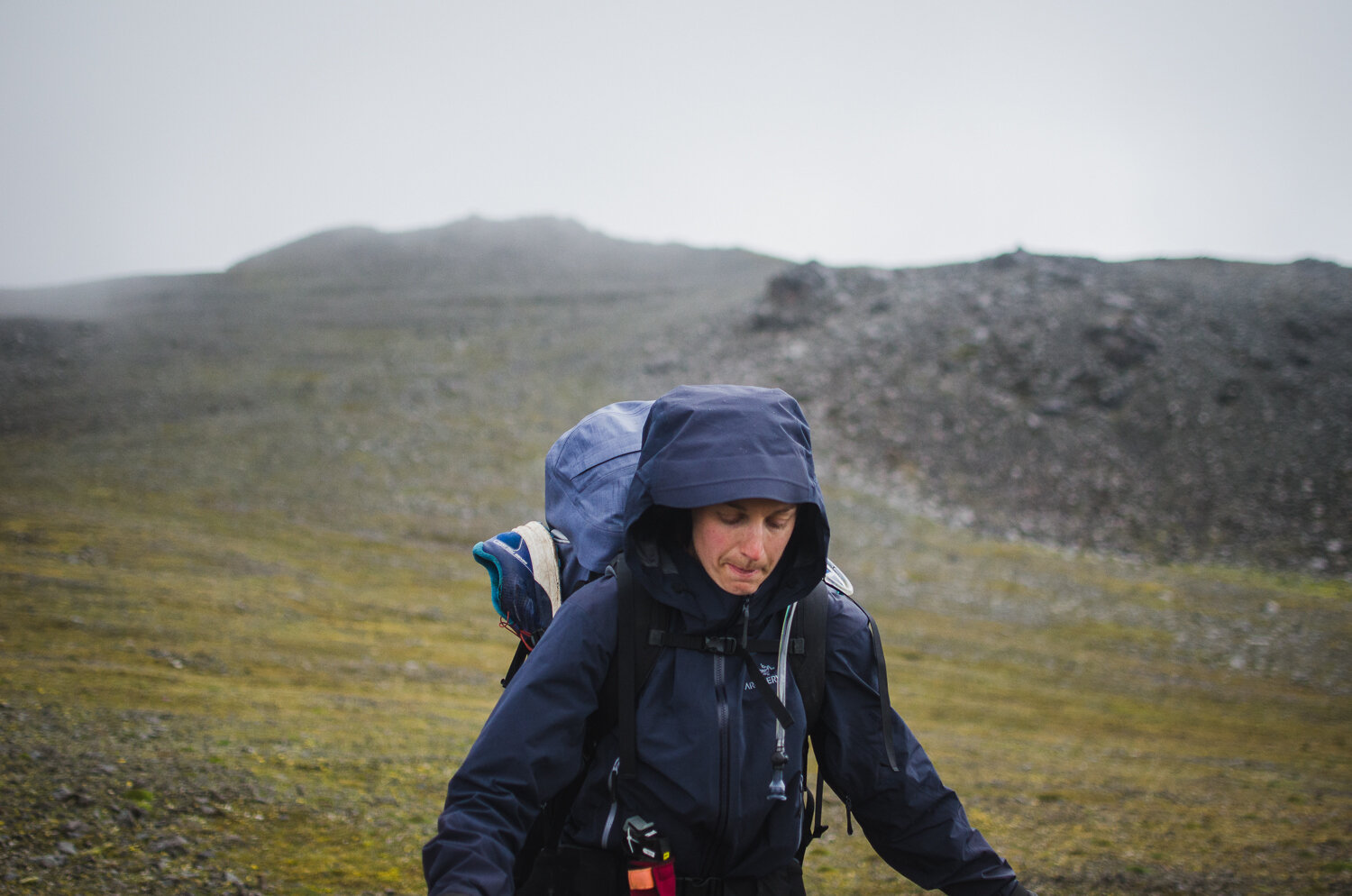

The next morning brought cold and mist to the day. Massive clouds were starting to roll in and we all wondered if we’d get rain later on. Little did we know; the clouds foreshadowed the difficult challenges we were about to face. By the end of the day, the rain had started and would not let up for the rest of the trip.

Hoge Pass

With clouds swirling around us we started up our first mountain pass, Hoge Pass. After some tricky navigation in marginal conditions, we made it down the other side and set up camp in a nice but buggy meadow. Cold and wet, we couldn’t wait to get to bed, but it was hard to get rest with the rain pounding on the tent fly. The next day, we begrudgingly put on our water saturated socks and boots and started off on an old horse trail. It was cool to see an old trail in such good shape and after 6 hours of hiking, we arrived at the mighty Donjek Glacier.

Arriving at the glacier was bittersweet. We were soaking wet, it felt arctic with daily highs around 4-6º Celsius, and we couldn’t see anything higher than a few hundred meters. It was pretty disappointing to be in one of the biggest mountain ranges in North America and not being able to see anything. It was increasingly hard to stay on top of these conditions and it felt like we were constantly on the brink of hypothermia. That evening we got a few hours of respite from the rain and so we made our way to the base of the glacier bundled up in all the warm clothes we had.

The Donjek Glacier is pretty incredible. It’s surrounded by this weird, silty/sandy/muddy wasteland leftover from the ever-changing landscape. As the glacier changes shape annually, it sometimes creates a plug that transforms the river into a lake. These constant changes make the landscape look like a massive mining operation. The glacier is also actively calving, with huge pieces of ice breaking off into the river. When these pieces crash down, it thunders across the valley and launches a massive wave towards the opposite shore. It’s an incredible sight to see.

The massive glacier walls of the Donjek

Expectation Pass

We had planned on staying an extra day at the glacier, but the weather forecast was only getting worse, so we decided to continue our journey the next day. Our next objective was Expectation Pass and it was going to test my navigation abilities to the limit. As we ascended a ridge that led to the pass, the weather closed in on us until we had about 30m of visibility. In this opaque fog, we noticed the steep scree slopes we were crossing were dropping off on either side of us. It was really stressful looking down and not knowing if the void below was 10m high or 100m and if the way forward would lead us to impassable terrain. We very carefully picked our way up the mountain and to our relief arrived at the easy, flat plateau of Expectation pass. As we cruised up and over the pass, we breathed a sigh of relief; camp was only 2km away over what I thought was easy terrain. Boy was I wrong.

The weather cleared up on the other side of the pass to reveal about four 50-100m high drainages and impassible canyons between us and our planned camp. Traveling the first 300m through and around the first few drainages took us forty-five minutes! We hiked for another hour until, 500m away from camp, we reached the cliffs of an untraversable canyon. Defeated, we set up camp in the pouring rain on the edge of the cliffs and pitched our tents on an angled and bumpy hillside. It wasn’t great, but the silver lining was that we were visited by a herd of Dall Sheep during dinner. It was the only redeeming part of this day.

Atlas Pass

The next morning, my heart sank as I opened the tent door. The snow line had dropped 2000’ and our tents were covered in snow. Today was the day we had to cross Atlas pass; the hardest pass on the route that is strongly not recommended in low visibility or rain. After talking about our options, we decided to go up carefully and turn around at any big signs of hazards. We packed our wet bags, took down our soaking tents, and crammed our frozen feet into slushy boots. It felt like a turning point to the trip as the energy shifted from miserable to survival. As we picked our way up to the pass, the snow deepened until we were punching into 20-30cm of snow. You could see the avalanche risk brewing with small point released debris paths and giant pinwheeling snowballs. We definitely did not want to stick around any longer that we had to. Suddenly, just to make things harder, 300m before the top of the pass, a giant grizzly bear materialized in the middle of where we had to go. After about 10 seconds of hooting and hollering, the bear looked up and started jogging towards us before disappearing behind a little hill. We all muttered “shit” under our breath and pulled the safety off our bear spray.

Thankfully, the bear re-emerged higher up and running for dear life away from us. We all relaxed a little bit and joked that the bear was leading us over the pass.

The misery of Atlas Pass

Gritting our teeth from cold and stress, we slowly navigated our way up and over Atlas pass kicking steps into the snow. The ground under the snow was very loose and crumbly, making for slow and laborious progress. As we descended from the snow line, we actually cheered when the snow turned to rain. Again, we breathed a sigh of relief thinking that the worst was over and again, we were all terribly wrong. The terrain turned from an easy, open ridge to steep scary scree slopes. We found a flat little patch of green grass (colloquially called the “Hole #9”) and set up a tarp for some quick lunch.

While we were trying to warm up with a cup of soup, a loud crack resounded above and a truck size boulder broke off the overhead cliff and hurtled down towards us. There was no time to do anything but yell “F•¢k!” and look on. The boulder blasted down about 20m away from us directly in our route down. While we stared in disbelief at what we had witnessed, more rocks started falling down on either side of the drainage we were supposed to hike in. At that moment, I felt stuck; there was no way I was going back up to snow covered Atlas pass, and I didn’t want to go down into an extremely dangerous rock shooting gallery. With no viable alternative, we crossed our fingers and half jogged down the next 1km with rocks landing around us. This experience is something I never want to go through again.

Three hours later after more bush whacking, endless side sloping and a slog through a tussocky wetland (imagine walking on a giant wet sponge), we arrived at a nice little creek with lots of camp options. The cloud thinned a little, the rain stopped and we felt overjoyed. The challenging passes were behind us and our car was an easy day and a half away. We thought the worst was behind us and goddamn, were we wrong again….

While we had planned for rain and had plenty of extra food and fuel, we didn’t account for historic rainfall. This past summer has seen record breaking rainfall in the Yukon and Kluane was no exception. Unbeknownst to us, the water levels had risen significantly and the Duke River had transformed into a raging, brown water torrent. Overnight, the rain started pounding our tents and we awoke the next day to dense fog and an incessant mix of drizzle and rain. We packed our bags and started making our way to the junction of Grizzly creek and the Duke river. Here, the river was very braided and in theory much shallower. After some fast walking on great game trails, we crossed the first few river braids without too much difficulty. However, the water was frigid and within minutes our feet were cold and swollen by the glacier fed waters. We crossed onto a gravel bar in the middle of the Duke River and started looking for a place to cross. After 20 minutes of searching Joya found a good looking, 15-meter-wide channel. Shivering and soaked to the bone, we made our way to the edge of the riverbank. The water was fast but it seemed to stay around knee high so we decided to attempt to cross in triangle formation. With Joya in front and Emma and I bracing her from behind we slowly marched sideways across the current, pushing with all our might against the water.

A swollen Slims River

Suddenly, the water rose up to our thighs and we could no longer move as a unit. Joya slipped and was grabbed by the rapids. As she was being swept downstream she could no longer move under the weight of her backpack and running out of options, wiggled out of her pack straps and half swam half crawled to the opposite river bank. Without the ability to lean on Joya for support, I also slipped and was swept downstream. I barely managed to keep my head above the water and hobbled to join Joya on the bank. Emma, left completely alone near the middle of the channel, made a herculean effort and managed to get back to the side of the channel without falling.

“My backpack, my backpack!!” yelled Joya and to our horror we turned and helplessly watched her backpack float away downstream. Emma sprinted to try to get it but there was no catching up to the pack. Joya and I were now split up from Emma on the far side of the river. There was no way it was safe for Emma to cross so Joya and I were left with no choice but to cross back. We managed to make it about halfway when my legs gave out and the current swept me again. The weight of my pack pushed my head and body underwater as I desperately tried to hobble/crawl/swim to the river bank. Luckily, thank god, Joya made it just in time to grab my pack and hold it steady while I crawled out of the water to shore. All three of us back together, we half ran and half limped back across the Duke river gravel bars and pitched camp on the first flat area we found.

I think it’s the fastest camp setup I’ve ever done. Even though I was violently shaking from the cold and had hands that were cut up, bleeding and almost too swollen to make a fist, we managed to pitch a tarp and a tent in about 3 minutes tops. Luck was on our side because between my pack and Emma’s, there were enough warm dry clothes and sleeping bags to cover all of us and our emergency communication device still worked.

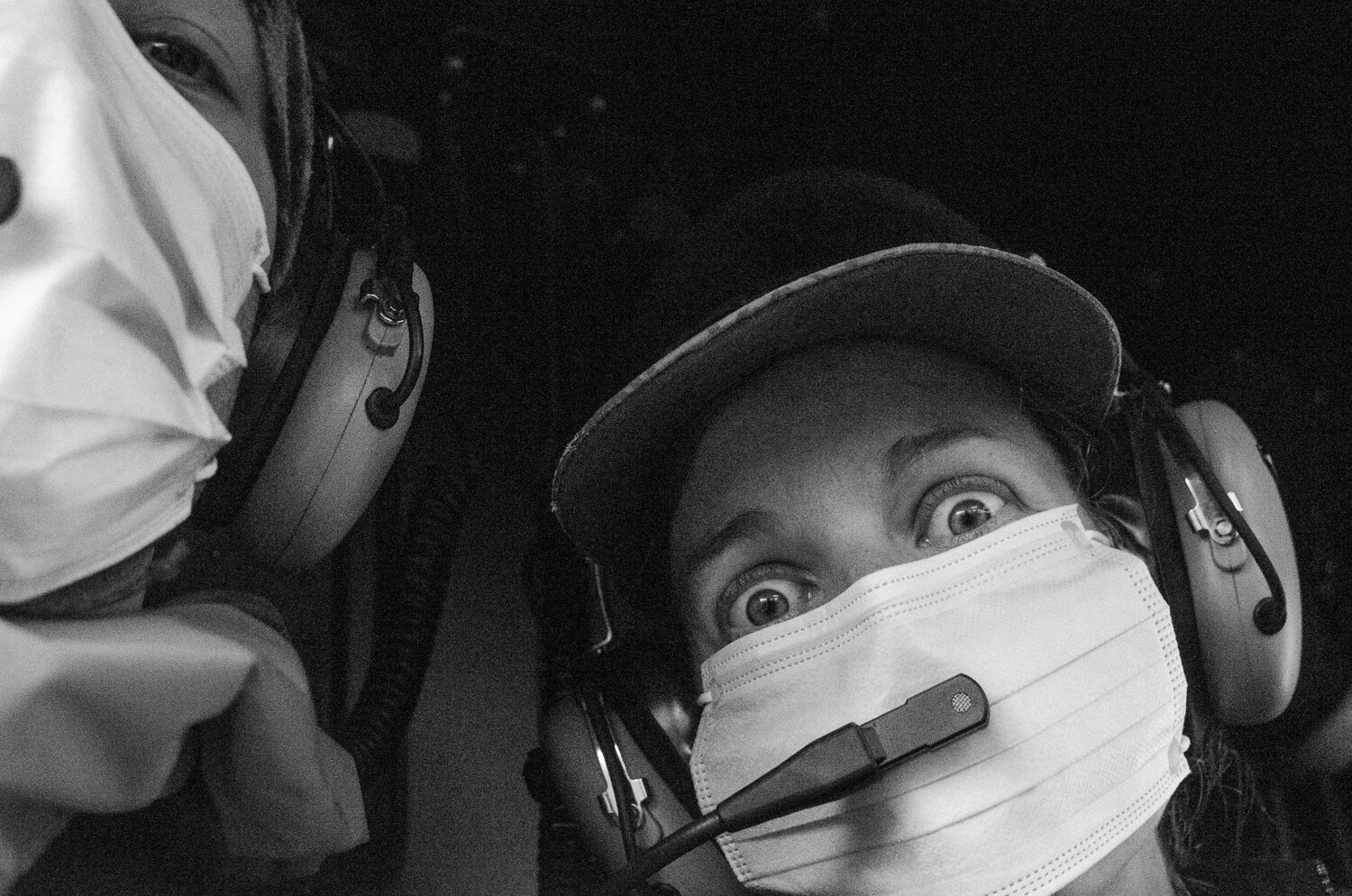

After Joya and I stopped shaking 40 minutes later, with three of us in my two-person tent, we accessed our losses. Joya had lost all her gear; sleeping bag, mat, and dry clothes. She was also carrying a third of the remaining food, most of the fuel, a repair kit and a solo tent. We contacted Parks Canada with our inReach and they recommended staying there for 48 hours to wait for water levels to drop. That would have meant stretching the 4 meals we had left with half a fuel bottle for 3-4 days. Feeling that it was cutting to thin any safety margin we had left, we pulled the plug and requested a rescue. Five hours later, in a disgusting mix of ironic bullshit, the rain stopped, the sky opened up to a beautiful day, and a park helicopter landed right nearby.

For the first time in seven days, we finally saw the mountains.